Up to date

This page is up to date for Godot 4.2.

If you still find outdated information, please open an issue.

Pokročilá vektorová matematika¶

Roviny¶

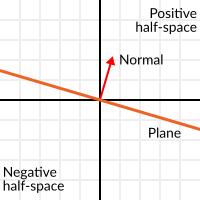

Skalární součin má jinou zajímavou vlastnost s jednotkovými vektory. Představte si, že kolmice na tento vektor (a skrz počátek) projde rovinou. Roviny rozdělují celý prostor na kladný (nad rovinou) a záporný (pod rovinou) a (na rozdíl od všeobecné domněnky), můžete použít jejich matematické operace i ve 2D:

Unit vectors that are perpendicular to a surface (so, they describe the orientation of the surface) are called unit normal vectors. Though, usually they are just abbreviated as normals. Normals appear in planes, 3D geometry (to determine where each face or vertex is siding), etc. A normal is a unit vector, but it's called normal because of its usage. (Just like we call (0,0) the Origin!).

The plane passes by the origin and the surface of it is perpendicular to the unit vector (or normal). The side towards the vector points to is the positive half-space, while the other side is the negative half-space. In 3D this is exactly the same, except that the plane is an infinite surface (imagine an infinite, flat sheet of paper that you can orient and is pinned to the origin) instead of a line.

Vzdálenost k rovině¶

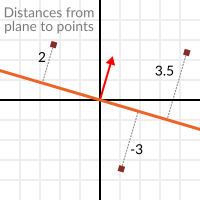

Nyní, když je zřejmé co je rovina, se podíváme zpět na skalární součin. Skalární součin mezi jednotkovým vektorem a nějakým bodem v prostoru (ano, tentokrát děláme skalární součin mezi vektorem a pozicí), vrátí vzdálenost od bodu k rovině:

var distance = normal.dot(point)

var distance = normal.Dot(point);

Ale ne jen absolutní vzdálenost, pokud se bod nachází v záporném poloprostoru, vzdálenost bude také záporná:

To nám umožňuje říct, na které straně roviny se bod nachází.

Pryč od počátku¶

Vím, na co myslíte! Zatím je to pěkné, ale skutečné roviny jsou všude v prostoru, nejen že procházejí počátkem. Chcete reálnou rovinu v akci a chcete ji hned.

Pamatujte, že roviny nejen rozdělují prostor na dvě části, ale mají také polaritu. To znamená, že je možné mít dokonale se překrývající roviny, ale jejich záporné a kladné poloprostory jsou přehozeny.

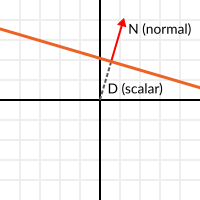

S ohledem na to, popíšeme celou roviny jako normálu N a skalár vzdálenost od počátku D. Naše rovina je tedy zastoupena N a D. Například:

Pro 3D matematiku poskytuje Godot vestavěný typ Plane, který se o to postará.

Basically, N and D can represent any plane in space, be it for 2D or 3D (depending on the amount of dimensions of N) and the math is the same for both. It's the same as before, but D is the distance from the origin to the plane, travelling in N direction. As an example, imagine you want to reach a point in the plane, you will just do:

var point_in_plane = N*D

var pointInPlane = N * D;

This will stretch (resize) the normal vector and make it touch the plane. This math might seem confusing, but it's actually much simpler than it seems. If we want to tell, again, the distance from the point to the plane, we do the same but adjusting for distance:

var distance = N.dot(point) - D

var distance = N.Dot(point) - D;

The same thing, using a built-in function:

var distance = plane.distance_to(point)

var distance = plane.DistanceTo(point);

This will, again, return either a positive or negative distance.

Flipping the polarity of the plane can be done by negating both N and D. This will result in a plane in the same position, but with inverted negative and positive half spaces:

N = -N

D = -D

N = -N;

D = -D;

Godot also implements this operator in Plane. So, using the format below will work as expected:

var inverted_plane = -plane

var invertedPlane = -plane;

So, remember, the plane's main practical use is that we can calculate the distance to it. So, when is it useful to calculate the distance from a point to a plane? Let's see some examples.

Constructing a plane in 2D¶

Planes clearly don't come out of nowhere, so they must be built. Constructing them in 2D is easy, this can be done from either a normal (unit vector) and a point, or from two points in space.

In the case of a normal and a point, most of the work is done, as the normal is already computed, so calculate D from the dot product of the normal and the point.

var N = normal

var D = normal.dot(point)

var N = normal;

var D = normal.Dot(point);

For two points in space, there are actually two planes that pass through them, sharing the same space but with normal pointing to the opposite directions. To compute the normal from the two points, the direction vector must be obtained first, and then it needs to be rotated 90° degrees to either side:

# Calculate vector from `a` to `b`.

var dvec = point_a.direction_to(point_b)

# Rotate 90 degrees.

var normal = Vector2(dvec.y, -dvec.x)

# Alternatively (depending the desired side of the normal):

# var normal = Vector2(-dvec.y, dvec.x)

// Calculate vector from `a` to `b`.

var dvec = pointA.DirectionTo(pointB);

// Rotate 90 degrees.

var normal = new Vector2(dvec.Y, -dvec.X);

// Alternatively (depending the desired side of the normal):

// var normal = new Vector2(-dvec.Y, dvec.X);

The rest is the same as the previous example. Either point_a or point_b will work, as they are in the same plane:

var N = normal

var D = normal.dot(point_a)

# this works the same

# var D = normal.dot(point_b)

var N = normal;

var D = normal.Dot(pointA);

// this works the same

// var D = normal.Dot(pointB);

Doing the same in 3D is a little more complex and is explained further down.

Some examples of planes¶

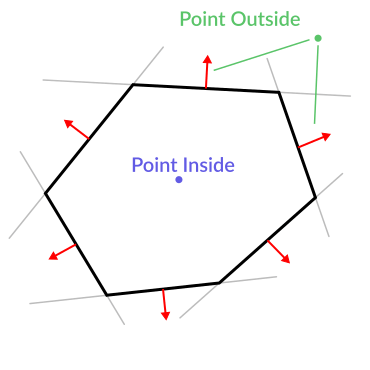

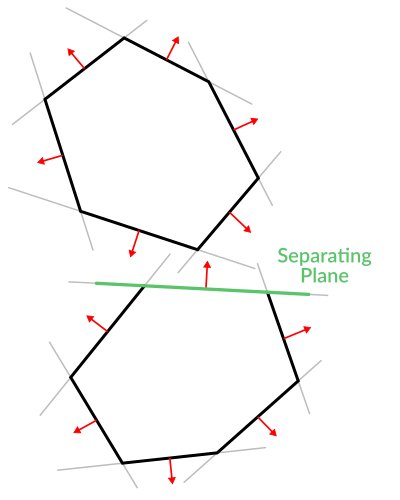

Here is an example of what planes are useful for. Imagine you have a convex polygon. For example, a rectangle, a trapezoid, a triangle, or just any polygon where no faces bend inwards.

For every segment of the polygon, we compute the plane that passes by that segment. Once we have the list of planes, we can do neat things, for example checking if a point is inside the polygon.

We go through all planes, if we can find a plane where the distance to the point is positive, then the point is outside the polygon. If we can't, then the point is inside.

Code should be something like this:

var inside = true

for p in planes:

# check if distance to plane is positive

if (p.distance_to(point) > 0):

inside = false

break # with one that fails, it's enough

var inside = true;

foreach (var p in planes)

{

// check if distance to plane is positive

if (p.DistanceTo(point) > 0)

{

inside = false;

break; // with one that fails, it's enough

}

}

Pretty cool, huh? But this gets much better! With a little more effort, similar logic will let us know when two convex polygons are overlapping too. This is called the Separating Axis Theorem (or SAT) and most physics engines use this to detect collision.

With a point, just checking if a plane returns a positive distance is enough to tell if the point is outside. With another polygon, we must find a plane where all the other polygon points return a positive distance to it. This check is performed with the planes of A against the points of B, and then with the planes of B against the points of A:

Code should be something like this:

var overlapping = true

for p in planes_of_A:

var all_out = true

for v in points_of_B:

if (p.distance_to(v) < 0):

all_out = false

break

if (all_out):

# a separating plane was found

# do not continue testing

overlapping = false

break

if (overlapping):

# only do this check if no separating plane

# was found in planes of A

for p in planes_of_B:

var all_out = true

for v in points_of_A:

if (p.distance_to(v) < 0):

all_out = false

break

if (all_out):

overlapping = false

break

if (overlapping):

print("Polygons Collided!")

var overlapping = true;

foreach (Plane plane in planesOfA)

{

var allOut = true;

foreach (Vector3 point in pointsOfB)

{

if (plane.DistanceTo(point) < 0)

{

allOut = false;

break;

}

}

if (allOut)

{

// a separating plane was found

// do not continue testing

overlapping = false;

break;

}

}

if (overlapping)

{

// only do this check if no separating plane

// was found in planes of A

foreach (Plane plane in planesOfB)

{

var allOut = true;

foreach (Vector3 point in pointsOfA)

{

if (plane.DistanceTo(point) < 0)

{

allOut = false;

break;

}

}

if (allOut)

{

overlapping = false;

break;

}

}

}

if (overlapping)

{

GD.Print("Polygons Collided!");

}

As you can see, planes are quite useful, and this is the tip of the iceberg. You might be wondering what happens with non convex polygons. This is usually just handled by splitting the concave polygon into smaller convex polygons, or using a technique such as BSP (which is not used much nowadays).

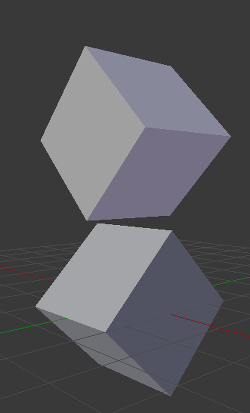

Collision detection in 3D¶

This is another bonus bit, a reward for being patient and keeping up with this long tutorial. Here is another piece of wisdom. This might not be something with a direct use case (Godot already does collision detection pretty well) but it's used by almost all physics engines and collision detection libraries :)

Remember that converting a convex shape in 2D to an array of 2D planes was useful for collision detection? You could detect if a point was inside any convex shape, or if two 2D convex shapes were overlapping.

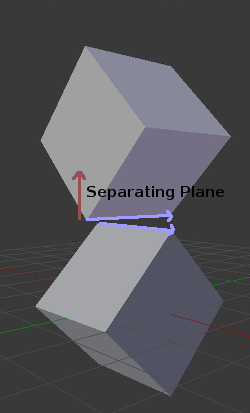

Well, this works in 3D too, if two 3D polyhedral shapes are colliding, you won't be able to find a separating plane. If a separating plane is found, then the shapes are definitely not colliding.

To refresh a bit a separating plane means that all vertices of polygon A are in one side of the plane, and all vertices of polygon B are in the other side. This plane is always one of the face-planes of either polygon A or polygon B.

In 3D though, there is a problem to this approach, because it is possible that, in some cases a separating plane can't be found. This is an example of such situation:

To avoid it, some extra planes need to be tested as separators, these planes are the cross product between the edges of polygon A and the edges of polygon B

So the final algorithm is something like:

var overlapping = true

for p in planes_of_A:

var all_out = true

for v in points_of_B:

if (p.distance_to(v) < 0):

all_out = false

break

if (all_out):

# a separating plane was found

# do not continue testing

overlapping = false

break

if (overlapping):

# only do this check if no separating plane

# was found in planes of A

for p in planes_of_B:

var all_out = true

for v in points_of_A:

if (p.distance_to(v) < 0):

all_out = false

break

if (all_out):

overlapping = false

break

if (overlapping):

for ea in edges_of_A:

for eb in edges_of_B:

var n = ea.cross(eb)

if (n.length() == 0):

continue

var max_A = -1e20 # tiny number

var min_A = 1e20 # huge number

# we are using the dot product directly

# so we can map a maximum and minimum range

# for each polygon, then check if they

# overlap.

for v in points_of_A:

var d = n.dot(v)

max_A = max(max_A, d)

min_A = min(min_A, d)

var max_B = -1e20 # tiny number

var min_B = 1e20 # huge number

for v in points_of_B:

var d = n.dot(v)

max_B = max(max_B, d)

min_B = min(min_B, d)

if (min_A > max_B or min_B > max_A):

# not overlapping!

overlapping = false

break

if (not overlapping):

break

if (overlapping):

print("Polygons collided!")

var overlapping = true;

foreach (Plane plane in planesOfA)

{

var allOut = true;

foreach (Vector3 point in pointsOfB)

{

if (plane.DistanceTo(point) < 0)

{

allOut = false;

break;

}

}

if (allOut)

{

// a separating plane was found

// do not continue testing

overlapping = false;

break;

}

}

if (overlapping)

{

// only do this check if no separating plane

// was found in planes of A

foreach (Plane plane in planesOfB)

{

var allOut = true;

foreach (Vector3 point in pointsOfA)

{

if (plane.DistanceTo(point) < 0)

{

allOut = false;

break;

}

}

if (allOut)

{

overlapping = false;

break;

}

}

}

if (overlapping)

{

foreach (Vector3 edgeA in edgesOfA)

{

foreach (Vector3 edgeB in edgesOfB)

{

var normal = edgeA.Cross(edgeB);

if (normal.Length() == 0)

{

continue;

}

var maxA = float.MinValue; // tiny number

var minA = float.MaxValue; // huge number

// we are using the dot product directly

// so we can map a maximum and minimum range

// for each polygon, then check if they

// overlap.

foreach (Vector3 point in pointsOfA)

{

var distance = normal.Dot(point);

maxA = Mathf.Max(maxA, distance);

minA = Mathf.Min(minA, distance);

}

var maxB = float.MinValue; // tiny number

var minB = float.MaxValue; // huge number

foreach (Vector3 point in pointsOfB)

{

var distance = normal.Dot(point);

maxB = Mathf.Max(maxB, distance);

minB = Mathf.Min(minB, distance);

}

if (minA > maxB || minB > maxA)

{

// not overlapping!

overlapping = false;

break;

}

}

if (!overlapping)

{

break;

}

}

}

if (overlapping)

{

GD.Print("Polygons Collided!");

}

Více informací¶

For more information on using vector math in Godot, see the following article:

If you would like additional explanation, you should check out 3Blue1Brown's excellent video series "Essence of Linear Algebra": https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fNk_zzaMoSs&list=PLZHQObOWTQDPD3MizzM2xVFitgF8hE_ab