Up to date

This page is up to date for Godot 4.2.

If you still find outdated information, please open an issue.

GDScript reference¶

GDScript is a high-level, object-oriented, imperative, and gradually typed programming language built for Godot. It uses an indentation-based syntax similar to languages like Python. Its goal is to be optimized for and tightly integrated with Godot Engine, allowing great flexibility for content creation and integration.

GDScript is entirely independent from Python and is not based on it.

Historique¶

Note

La documentation sur l'histoire de GDScript a été déplacée dans Questions fréquentes.

Exemple de GDScript¶

Some people can learn better by taking a look at the syntax, so here's an example of how GDScript looks.

# Everything after "#" is a comment.

# A file is a class!

# (optional) icon to show in the editor dialogs:

@icon("res://path/to/optional/icon.svg")

# (optional) class definition:

class_name MyClass

# Inheritance:

extends BaseClass

# Member variables.

var a = 5

var s = "Hello"

var arr = [1, 2, 3]

var dict = {"key": "value", 2: 3}

var other_dict = {key = "value", other_key = 2}

var typed_var: int

var inferred_type := "String"

# Constants.

const ANSWER = 42

const THE_NAME = "Charly"

# Enums.

enum {UNIT_NEUTRAL, UNIT_ENEMY, UNIT_ALLY}

enum Named {THING_1, THING_2, ANOTHER_THING = -1}

# Built-in vector types.

var v2 = Vector2(1, 2)

var v3 = Vector3(1, 2, 3)

# Functions.

func some_function(param1, param2, param3):

const local_const = 5

if param1 < local_const:

print(param1)

elif param2 > 5:

print(param2)

else:

print("Fail!")

for i in range(20):

print(i)

while param2 != 0:

param2 -= 1

match param3:

3:

print("param3 is 3!")

_:

print("param3 is not 3!")

var local_var = param1 + 3

return local_var

# Functions override functions with the same name on the base/super class.

# If you still want to call them, use "super":

func something(p1, p2):

super(p1, p2)

# It's also possible to call another function in the super class:

func other_something(p1, p2):

super.something(p1, p2)

# Inner class

class Something:

var a = 10

# Constructor

func _init():

print("Constructed!")

var lv = Something.new()

print(lv.a)

Si vous avez déjà de l’expérience avec des langages à typage statique tels que C, C++ ou C# mais que vous n'avez jamais utilisé un langage à typage dynamique, il vous est conseillé de lire ce tutoriel : GDScript : Une introduction aux langages dynamiques.

Langage¶

Ce qui suit est un aperçu de GDScript. Les détails tels que les méthodes disponibles pour les tableaux ou autres objets peuvent être consultés dans les liens vers les descriptions des classes.

Identifiants¶

Toute chaîne de caractère limitée aux caractères alphabétiques (a à z et A à Z), aux chiffres (0 à 9) et _ est un identifiant potentiel. Les identifiants ne doivent également pas commencer par un chiffre. Les identifiants sont sensibles à la casse. (toto est différent de TOTO).

Identifiers may also contain most Unicode characters part of UAX#31. This allows you to use identifier names written in languages other than English. Unicode characters that are considered "confusable" for ASCII characters and emoji are not allowed in identifiers.

Mots-clés¶

Ce qui suit est une liste de mots-clés supportés par le langage. Étant donné que les mots-clés sont des mots (symboles) réservés, il ne peuvent êtres utilisés comme identifiants. Les opérateurs (comme in, not, and ou or) et les noms des types intégrés énumérés dans les sections suivantes sont également réservés.

Les mots-clés sont définis dans le GDScript tokenizer si vous souhaitez regarder sous le capot.

Mot-clé |

Description |

|---|---|

if |

Voir if/else/elif. |

elif |

Voir if/else/elif. |

else |

Voir if/else/elif. |

for |

Voir for. |

while |

Voir while. |

match |

Voir match. |

break |

Quitte l'exécution de la boucle |

continue |

Passe immédiatement à l'itération suivante de la boucle |

pass |

Utilisé lorsqu'une instruction est requise syntaxiquement mais où l’exécution de code est indésirable, comme par exemple, dans une fonction vide. |

return |

Retourne une valeur à partir d'une fonction. |

class |

Defines an inner class. See Inner classes. |

class_name |

Defines the script as a globally accessible class with the specified name. See Registering named classes. |

extends |

Définit quelle classe étendre avec la classe courante. |

is |

Teste si une variable est du type d'une classe donnée, ou si elle est d'un type intégré donnée. |

in |

Tests whether a value is within a string, array, range, dictionary, or node. When used with |

as |

Convertir la valeur vers un type donné, si possible. |

self |

Réfère à l'instance courante de la classe. |

signal |

Définit un signal. |

func |

Définit une fonction. |

static |

Defines a static function or a static member variable. |

const |

Définit une constante. |

enum |

Définit une énumération. |

var |

Définit une variable. |

breakpoint |

Editor helper for debugger breakpoints. Unlike breakpoints created by clicking in the gutter, |

preload |

Précharge une classe ou une variable. Voir Classes as resources. |

await |

Waits for a signal or a coroutine to finish. See Awaiting for signals or coroutines. |

yield |

Previously used for coroutines. Kept as keyword for transition. |

assert |

Affirmer une condition, journalise les erreurs en cas d'échec. Ignorer dans les compilations autre que de débogages. Voir Assert keyword. |

void |

Used to represent that a function does not return any value. |

PI |

Constante PI. |

TAU |

Constante TAU. |

INF |

Infinity constant. Used for comparisons and as result of calculations. |

NAN |

NAN (not a number) constant. Used as impossible result from calculations. |

Opérateurs¶

Ce qui suit est la liste des opérateurs supportés et leur priorité.

Opérateur |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Grouping (highest priority) Parentheses are not really an operator, but allow you to explicitly specify the precedence of an operation. |

|

Subscription |

|

Référence d'attribut |

|

Appel de fonction |

|

|

|

Type checking See also is_instance_of() function. |

|

Power Multiplies Note: In GDScript, the |

|

Opération bit-à-bit de négation |

+x-x |

Identity / Negation |

x * yx / yx % y |

Multiplication / Division / Reste The Note: These operators have the same behavior as C++, which may be unexpected for users coming from Python, JavaScript, etc. See a detailed note after the table. |

x + yx - y |

Addition (or Concatenation) / Subtraction |

x << yx >> y |

Décalage de bits |

|

Conjonction logique bit-à-bit |

|

Opération "Ou" exclusif bit-à-bit |

|

Disjonction logique bit-à-bit |

x == yx != yx < yx > yx <= yx >= y |

Comparison See a detailed note after the table. |

x in yx not in y |

Inclusion checking

|

not x!x |

Boolean NOT and its unrecommended alias |

x and yx && y |

Boolean AND and its unrecommended alias |

x or yx || y |

Boolean OR and its unrecommended alias |

|

if / else ternaire |

|

|

x = yx += yx -= yx *= yx /= yx **= yx %= yx &= yx |= yx ^= yx <<= yx >>= y |

Affectation (priorité la plus basse) You cannot use an assignment operator inside an expression. |

Note

The behavior of some operators may differ from what you expect:

If both operands of the

/operator are int, then integer division is performed instead of fractional. For example5 / 2 == 2, not2.5. If this is not desired, use at least one float literal (x / 2.0), cast (float(x) / y), or multiply by1.0(x * 1.0 / y).The

%operator is only available for ints, for floats use the fmod() function.For negative values, the

%operator andfmod()use truncation instead of rounding towards negative infinity. This means that the remainder has a sign. If you need the remainder in a mathematical sense, use the posmod() and fposmod() functions instead.The

**operator is left-associative. This means that2 ** 2 ** 3is equal to(2 ** 2) ** 3. Use parentheses to explicitly specify precedence you need, for example2 ** (2 ** 3).The

==and!=operators sometimes allow you to compare values of different types (for example,1 == 1.0is true), but in other cases it can cause a runtime error. If you're not sure about the types of the operands, you can safely use the is_same() function (but note that it is more strict about types and references). To compare floats, use the is_equal_approx() and is_zero_approx() functions instead.

Littéraux¶

Example(s) |

Description |

|

Null value |

|

Boolean values |

|

Entier en base 10 (décimal) |

|

Entier base 16 (hexadécimal) |

|

Entier base 2 (binaire) |

|

Nombre à virgule flottante (réel) |

|

Regular strings |

|

Triple-quoted regular strings |

|

Raw strings |

|

Triple-quoted raw strings |

|

|

|

There are also two constructs that look like literals, but actually are not:

Exemple |

Description |

|

Sténographie pour |

|

Shorthand for |

Les nombres entiers et les nombres flottants peuvent être séparés par des _ pour les rendre plus lisibles. Les manières suivantes d'écrire les nombres sont toutes valables :

12_345_678 # Equal to 12345678.

3.141_592_7 # Equal to 3.1415927.

0x8080_0000_ffff # Equal to 0x80800000ffff.

0b11_00_11_00 # Equal to 0b11001100.

Regular string literals can contain the following escape sequences:

Séquence d'échappement |

S’étend à |

|

Nouvelle ligne (line feed) |

|

Caractère de tabulation horizontale |

|

Retour chariot |

|

Alerte (bip/cloche) |

|

Effacer |

|

Saut de page Formfeed |

|

Caractère de tabulation verticale |

|

Guillemet |

|

Citation unique |

|

Antislash |

|

UTF-16 Unicode codepoint

|

|

UTF-32 Unicode codepoint

|

There are two ways to represent an escaped Unicode character above 0xFFFF:

as a UTF-16 surrogate pair

\uXXXX\uXXXX.as a single UTF-32 codepoint

\UXXXXXX.

Also, using \ followed by a newline inside a string will allow you to continue it in the next line,

without inserting a newline character in the string itself.

A string enclosed in quotes of one type (for example ") can contain quotes of another type

(for example ') without escaping. Triple-quoted strings allow you to avoid escaping up to

two consecutive quotes of the same type (unless they are adjacent to the string edges).

Raw string literals always encode the string as it appears in the source code. This is especially useful for regular expressions. Raw strings do not process escape sequences, but you can "escape" a quote or backslash (they replace themselves).

print("\tchar=\"\\t\"") # Prints ` char="\t"`.

print(r"\tchar=\"\\t\"") # Prints `\tchar=\"\\t\"`.

GDScript also supports format strings.

Annotations¶

There are some special tokens in GDScript that act like keywords but are not,

they are annotations instead. Every annotation start with the @ character

and is specified by a name. A detailed description and example for each annotation

can be found inside the GDScript class reference.

Annotations affect how the script is treated by external tools and usually don't change the behavior.

For instance, you can use it to export a value to the editor:

@export_range(1, 100, 1, "or_greater")

var ranged_var: int = 50

For more information about exporting properties, read the GDScript exports article.

Any constant expression compatible with the required argument type can be passed as an annotation argument value:

const MAX_SPEED = 120.0

@export_range(0.0, 0.5 * MAX_SPEED)

var initial_speed: float = 0.25 * MAX_SPEED

Annotations can be specified one per line or all in the same line. They affect the next statement that isn't an annotation. Annotations can have arguments sent between parentheses and separated by commas.

Both of these are the same:

@annotation_a

@annotation_b

var variable

@annotation_a @annotation_b var variable

@onready annotation¶

Lors de l'utilisation de nœuds, il est très courant de vouloir garder des références à des parties de la scène dans une variable. Comme les scènes ne peuvent être configurées que lors de l'entrée dans l'arbre des scènes actives, les sous-nœuds ne peuvent être obtenus que lorsqu'un appel à Node._ready() est fait.

var my_label

func _ready():

my_label = get_node("MyLabel")

This can get a little cumbersome, especially when nodes and external

references pile up. For this, GDScript has the @onready annotation, that

defers initialization of a member variable until _ready() is called. It

can replace the above code with a single line:

@onready var my_label = get_node("MyLabel")

Avertissement

Applying @onready and any @export annotation to the same variable

doesn't work as you might expect. The @onready annotation will cause

the default value to be set after the @export takes effect and will

override it:

@export var a = "init_value_a"

@onready @export var b = "init_value_b"

func _init():

prints(a, b) # init_value_a <null>

func _notification(what):

if what == NOTIFICATION_SCENE_INSTANTIATED:

prints(a, b) # exported_value_a exported_value_b

func _ready():

prints(a, b) # exported_value_a init_value_b

Therefore, the ONREADY_WITH_EXPORT warning is generated, which is treated

as an error by default. We do not recommend disabling or ignoring it.

Code regions¶

Code regions are special types of comments that the script editor understands as foldable regions. This means that after writing code region comments, you can collapse and expand the region by clicking the arrow that appears at the left of the comment. This arrow appears within a purple square to be distinguishable from standard code folding.

The syntax is as follows:

# Important: There must be *no* space between the `#` and `region` or `endregion`.

# Region without a description:

#region

...

#endregion

# Region with a description:

#region Some description that is displayed even when collapsed

...

#endregion

Astuce

To create a code region quickly, select several lines in the script editor, right-click the selection then choose Create Code Region. The region description will be selected automatically for editing.

It is possible to nest code regions within other code regions.

Here's a concrete usage example of code regions:

# This comment is outside the code region. It will be visible when collapsed.

#region Terrain generation

# This comment is inside the code region. It won't be visible when collapsed.

func generate_lakes():

pass

func generate_hills():

pass

#endregion

#region Terrain population

func place_vegetation():

pass

func place_roads():

pass

#endregion

This can be useful to organize large chunks of code into easier to understand sections. However, remember that external editors generally don't support this feature, so make sure your code is easy to follow even when not relying on folding code regions.

Note

Individual functions and indented sections (such as if and for) can

always be collapsed in the script editor. This means you should avoid

using a code region to contain a single function or indented section, as it

won't bring much of a benefit. Code regions work best when they're used to

group multiple elements together.

Line continuation¶

A line of code in GDScript can be continued on the next line by using a backslash

(\). Add one at the end of a line and the code on the next line will act like

it's where the backslash is. Here is an example:

var a = 1 + \

2

A line can be continued multiple times like this:

var a = 1 + \

4 + \

10 + \

4

Types intégrés¶

Built-in types are stack-allocated. They are passed as values. This means a copy

is created on each assignment or when passing them as arguments to functions.

The exceptions are Object, Array, Dictionary, and packed arrays

(such as PackedByteArray), which are passed by reference so they are shared.

All arrays, Dictionary, and some objects (Node, Resource)

have a duplicate() method that allows you to make a copy.

Types intégrés basiques¶

Une variable en GDScript peut être affectée à divers types intégrés.

null¶

null est une donnée vide qui ne contient aucune information et à laquelle aucune autre valeur ne peut être affectée.

bool¶

Abrégé de "boolean", il ne peut contenir que true ou false.

int¶

Short for "integer", it stores whole numbers (positive and negative).

It is stored as a 64-bit value, equivalent to int64_t in C++.

float¶

Stores real numbers, including decimals, using floating-point values.

It is stored as a 64-bit value, equivalent to double in C++.

Note: Currently, data structures such as Vector2, Vector3, and

PackedFloat32Array store 32-bit single-precision float values.

String¶

A sequence of characters in Unicode format.

StringName¶

An immutable string that allows only one instance of each name. They are slower to create and may result in waiting for locks when multithreading. In exchange, they're very fast to compare, which makes them good candidates for dictionary keys.

NodePath¶

A pre-parsed path to a node or a node property. It can be easily assigned to, and from, a String. They are useful to interact with the tree to get a node, or affecting properties like with Tweens.

Types intégrés vectoriels¶

Vector2¶

Type de vecteur 2D contenant les attributs x and y. Peut aussi être accédé comme pour un tableau.

Vector2i¶

Same as a Vector2 but the components are integers. Useful for representing items in a 2D grid.

Rect2¶

Type de rectangle 2D contenant deux champs de vecteurs : position et size. Contient également un champ end qui est position + size.

Vector3¶

Type de vecteur 3D contenant les attributs x, y et z. Il peut également être accédé comme un tableau.

Vector3i¶

Same as Vector3 but the components are integers. Can be use for indexing items in a 3D grid.

Transform2D¶

Matrice 3x2 utilisée pour les transformations 2D.

Plane¶

Plan 3D normalisé contenant un vecteur normal et une distance scalaire d.

Quaternion¶

Un quaternion est un type de données utilisé pour représenter une rotation 3D. Cette représentation est utile pour l'interpolation de rotations.

AABB¶

La boite englobante (ou 3D box) alignée par axe contient 2 champs de vecteurs : position et size. Contient également un champ end qui est position + size.

Basis¶

Matrice 3x3 utilisée pour les rotations 3D et les mises à l'échelle. Elle contient 3 attributs vecteurs (x, y et z) et peut aussi être accédé comme un tableae de vecteurs 3D.

Transform3D¶

Transformation 3D contenant un attribut base vectorielle basis et un attribut vecteur 3D (Vector3) origin.

Types intégrés dans le moteur¶

Color¶

Le type de données Color contient les attributs r, g, b, et a. Il peut aussi être accédé par h, s, et v pour la teinte(hue)/saturation/valeur.

RID¶

Identifiant de ressource (RID). Les serveurs utilisent des RIDs génériques pour référencer des données opaques.

Object¶

Classe de base pour tout ce qui n'est pas un type intégré.

Types de conteneurs intégrés¶

Array¶

Séquence générique de types d'objets arbitraires. Sont inclus d'autres tableaux ou dictionnaires (voir ci-dessous). Le tableau peut être redimensionné dynamiquement. Les tableaux sont indexés en commençant par l'index 0. Les indices négatifs comptent à partir de la fin.

var arr = []

arr = [1, 2, 3]

var b = arr[1] # This is 2.

var c = arr[arr.size() - 1] # This is 3.

var d = arr[-1] # Same as the previous line, but shorter.

arr[0] = "Hi!" # Replacing value 1 with "Hi!".

arr.append(4) # Array is now ["Hi!", 2, 3, 4].

Typed arrays¶

Godot 4.0 added support for typed arrays. On write operations, Godot checks that

element values match the specified type, so the array cannot contain invalid values.

The GDScript static analyzer takes typed arrays into account, however array methods like

front() and back() still have the Variant return type.

Typed arrays have the syntax Array[Type], where Type can be any Variant type,

native or user class, or enum. Nested array types (like Array[Array[int]]) are not supported.

var a: Array[int]

var b: Array[Node]

var c: Array[MyClass]

var d: Array[MyEnum]

var e: Array[Variant]

Array and Array[Variant] are the same thing.

Note

Arrays are passed by reference, so the array element type is also an attribute of the in-memory structure referenced by a variable in runtime. The static type of a variable restricts the structures that it can reference to. Therefore, you cannot assign an array with a different element type, even if the type is a subtype of the required type.

If you want to convert a typed array, you can create a new array and use the Array.assign() method:

var a: Array[Node2D] = [Node2D.new()]

# (OK) You can add the value to the array because `Node2D` extends `Node`.

var b: Array[Node] = [a[0]]

# (Error) You cannot assign an `Array[Node2D]` to an `Array[Node]` variable.

b = a

# (OK) But you can use the `assign()` method instead. Unlike the `=` operator,

# the `assign()` method copies the contents of the array, not the reference.

b.assign(a)

The only exception was made for the Array (Array[Variant]) type, for user convenience

and compatibility with old code. However, operations on untyped arrays are considered unsafe.

Packed arrays¶

Les tableaux GDScript sont alloués en mémoire de façon linéaire pour les performances. Les tableaux de très grosse taille (plus d'une dizaine de milliers d’éléments) peuvent cependant provoquer une fragmentation de la mémoire. S'il s'agit d'un problème à considérer, des types de tableaux spéciaux sont disponibles. Ceux-ci n'acceptent qu'un seul type de données. Ils permettent d’éviter une fragmentation de la mémoire, utilisent moins de mémoire, mais sont atomiques et ont tendance à être moins performants que les tableaux génériques. Leur usage n'est donc recommandé que pour de très larges ensembles de données :

PackedByteArray: An array of bytes (integers from 0 to 255).

PackedInt32Array: An array of 32-bit integers.

PackedInt64Array: An array of 64-bit integers.

PackedFloat32Array: An array of 32-bit floats.

PackedFloat64Array: An array of 64-bit floats.

PackedStringArray: An array of strings.

PackedVector2Array: An array of Vector2 values.

PackedVector3Array: An array of Vector3 values.

PackedColorArray: An array of Color values.

Dictionary¶

Conteneur associatif qui contient des valeurs référencées par des clés uniques.

var d = {4: 5, "A key": "A value", 28: [1, 2, 3]}

d["Hi!"] = 0

d = {

22: "value",

"some_key": 2,

"other_key": [2, 3, 4],

"more_key": "Hello"

}

Lua-style table syntax is also supported. Lua-style uses = instead of :

and doesn't use quotes to mark string keys (making for slightly less to write).

However, keys written in this form can't start with a digit (like any GDScript

identifier), and must be string literals.

var d = {

test22 = "value",

some_key = 2,

other_key = [2, 3, 4],

more_key = "Hello"

}

Pour ajouter une clé à un dictionnaire existant, accédez-y comme une clé existante et affectez lui une valeur :

var d = {} # Create an empty Dictionary.

d.waiting = 14 # Add String "waiting" as a key and assign the value 14 to it.

d[4] = "hello" # Add integer 4 as a key and assign the String "hello" as its value.

d["Godot"] = 3.01 # Add String "Godot" as a key and assign the value 3.01 to it.

var test = 4

# Prints "hello" by indexing the dictionary with a dynamic key.

# This is not the same as `d.test`. The bracket syntax equivalent to

# `d.test` is `d["test"]`.

print(d[test])

Note

La syntaxe des crochets peut être utilisée pour accéder aux propriétés de n'importe quel Object, et pas seulement aux Dictionnaires. N'oubliez pas qu'elle provoquera une erreur de script lorsque vous tenterez d'indexer une propriété inexistante. Pour éviter cela, utilisez les méthodes Object.get() et Object.set() à la place.

Signal¶

A signal is a message that can be emitted by an object to those who want to listen to it. The Signal type can be used for passing the emitter around.

Signals are better used by getting them from actual objects, e.g. $Button.button_up.

Callable¶

Contains an object and a function, which is useful for passing functions as values (e.g. when connecting to signals).

Getting a method as a member returns a callable. var x = $Sprite2D.rotate

will set the value of x to a callable with $Sprite2D as the object and

rotate as the method.

You can call it using the call method: x.call(PI).

Données¶

Variables¶

Les variables peuvent exister en tant que membres de la classe ou locales aux fonctions. Elles sont créées avec le mot-clé var et peuvent, éventuellement, se voir attribuer une valeur à l'initialisation.

var a # Data type is 'null' by default.

var b = 5

var c = 3.8

var d = b + c # Variables are always initialized in order.

Les variables peuvent optionnellement avoir une spécification de type. Lorsqu'un type est spécifié, la variable sera obligée d'avoir toujours le même type, et essayer d'assigner une valeur incompatible entraînera une erreur.

Les types sont spécifiés dans la variable par un : après le nom de la variable, suivi par le type.

var my_vector2: Vector2

var my_node: Node = Sprite2D.new()

Si la variable est initialisée dans la déclaration, le type peut être déduit, il est donc possible de ne pas mettre le nom du type :

var my_vector2 := Vector2() # 'my_vector2' is of type 'Vector2'.

var my_node := Sprite2D.new() # 'my_node' is of type 'Sprite2D'.

L'inférence de type n'est possible que si la valeur affectée a un type défini, sinon une erreur sera générée.

Les types valides sont :

Types intégrés (Array, Vector2, int, String, etc.).

Classes du moteur (Node, Resource, Reference, etc.).

Les noms des constantes s'ils contiennent un script ressource (

MyScriptsi vous avez déclaréconst MyScript = preload("res://my_script.gd")).D'autres classes dans le même script, respectant la portée (

InnerClass.NestedClasssi vous avez déclaréclass NestedClassà l'intérieur declass InnerClassdans la même portée).Les classes de script déclarées avec le mot-clé

class_name.Autoloads registered as singletons.

Note

While Variant is a valid type specification, it's not an actual type. It

only means there's no set type and is equivalent to not having a static type

at all. Therefore, inference is not allowed by default for Variant,

since it's likely a mistake.

You can turn off this check, or make it only a warning, by changing it in the project settings. See Système d’avertissement de GDScript for details.

Static variables¶

A class member variable can be declared static:

static var a

Static variables belong to the class, not instances. This means that static variables share values between multiple instances, unlike regular member variables.

From inside a class, you can access static variables from any function, both static and non-static. From outside the class, you can access static variables using the class or an instance (the second is not recommended as it is less readable).

Note

The @export and @onready annotations cannot be applied to a static variable.

Local variables cannot be static.

The following example defines a Person class with a static variable named max_id.

We increment the max_id in the _init() function. This makes it easy to keep track

of the number of Person instances in our game.

# person.gd

class_name Person

static var max_id = 0

var id

var name

func _init(p_name):

max_id += 1

id = max_id

name = p_name

In this code, we create two instances of our Person class and check that the class

and every instance have the same max_id value, because the variable is static and accessible to every instance.

# test.gd

extends Node

func _ready():

var person1 = Person.new("John Doe")

var person2 = Person.new("Jane Doe")

print(person1.id) # 1

print(person2.id) # 2

print(Person.max_id) # 2

print(person1.max_id) # 2

print(person2.max_id) # 2

Static variables can have type hints, setters and getters:

static var balance: int = 0

static var debt: int:

get:

return -balance

set(value):

balance = -value

A base class static variable can also be accessed via a child class:

class A:

static var x = 1

class B extends A:

pass

func _ready():

prints(A.x, B.x) # 1 1

A.x = 2

prints(A.x, B.x) # 2 2

B.x = 3

prints(A.x, B.x) # 3 3

@static_unload annotation¶

Since GDScript classes are resources, having static variables in a script prevents it from being unloaded even if there are no more instances of that class and no other references left. This can be important if static variables store large amounts of data or hold references to other project resources, such as scenes. You should clean up this data manually, or use the @static_unload annotation if static variables don't store important data and can be reset.

Avertissement

Currently, due to a bug, scripts are never freed, even if @static_unload annotation is used.

Note that @static_unload applies to the entire script (including inner classes)

and must be placed at the top of the script, before class_name and extends:

@static_unload

class_name MyNode

extends Node

See also Static functions and Static constructor.

Conversion de type¶

Les valeurs affectées à des variables typées doivent avoir un type compatible. S'il est nécessaire de contraindre une valeur à être d'un certain type, surtout pour les types d'objet, vous pouvez utiliser l'opérateur de conversion as.

La conversion de types d'objets résulte en le même objet si la valeur est du même type ou d'un type enfant du type de conversion.

var my_node2D: Node2D

my_node2D = $Sprite2D as Node2D # Works since Sprite2D is a subtype of Node2D.

Si la valeur n'est pas un type enfant, l'opération de conversion se résultera en une valeur null.

var my_node2D: Node2D

my_node2D = $Button as Node2D # Results in 'null' since a Button is not a subtype of Node2D.

Pour les types intégrés, ils seront convertis de force si possible, sinon le moteur générera une erreur.

var my_int: int

my_int = "123" as int # The string can be converted to int.

my_int = Vector2() as int # A Vector2 can't be converted to int, this will cause an error.

Le casting est également utile pour avoir de meilleures variables de type-safe lors de l’interaction avec l’arbre de la scène :

# Will infer the variable to be of type Sprite2D.

var my_sprite := $Character as Sprite2D

# Will fail if $AnimPlayer is not an AnimationPlayer, even if it has the method 'play()'.

($AnimPlayer as AnimationPlayer).play("walk")

Constantes¶

Les constantes sont des valeurs que vous ne pouvez pas changer lorsque le jeu est s’exécute. Leur valeur doit être connue au moment de la compilation. L'utilisation du mot-clé const permet de donner un nom à une valeur constante. Si vous essayez d'attribuer une valeur à une constante après qu'elle ait été déclarée, vous obtiendrez une erreur.

Nous recommandons d'utiliser des constantes chaque fois qu'une valeur n'est pas censée changer.

const A = 5

const B = Vector2(20, 20)

const C = 10 + 20 # Constant expression.

const D = Vector2(20, 30).x # Constant expression: 20.

const E = [1, 2, 3, 4][0] # Constant expression: 1.

const F = sin(20) # 'sin()' can be used in constant expressions.

const G = x + 20 # Invalid; this is not a constant expression!

const H = A + 20 # Constant expression: 25 (`A` is a constant).

Même si le type des constantes est implicitement spécifié par la valeur assignée, il est également possible d'ajouter une spécification explicite du type :

const A: int = 5

const B: Vector2 = Vector2()

Assigner une valeur à un type incompatible va générer une erreur.

You can also create constants inside a function, which is useful to name local magic values.

Note

Since objects, arrays and dictionaries are passed by reference, constants are "flat". This means that if you declare a constant array or dictionary, it can still be modified afterwards. They can't be reassigned with another value though.

Énumérations¶

Les énumérations sont en fait une forme abrégée pour déclarer des constantes, et sont pratiques si vous voulez assigner des entiers consécutifs à certaines constantes.

enum {TILE_BRICK, TILE_FLOOR, TILE_SPIKE, TILE_TELEPORT}

# Is the same as:

const TILE_BRICK = 0

const TILE_FLOOR = 1

const TILE_SPIKE = 2

const TILE_TELEPORT = 3

If you pass a name to the enum, it will put all the keys inside a constant Dictionary of that name. This means all constant methods of a dictionary can also be used with a named enum.

Important

Keys in a named enum are not registered

as global constants. They should be accessed prefixed

by the enum's name (Name.KEY).

enum State {STATE_IDLE, STATE_JUMP = 5, STATE_SHOOT}

# Is the same as:

const State = {STATE_IDLE = 0, STATE_JUMP = 5, STATE_SHOOT = 6}

func _ready():

# Access values with Name.KEY, prints '5'

print(State.STATE_JUMP)

# Use constant dictionary functions

# prints '["STATE_IDLE", "STATE_JUMP", "STATE_SHOOT"]'

print(State.keys())

Fonctions¶

Les fonctions appartiennent toujours à une classe. La priorité de portée pour la recherche de la variable est : locale → membre de classe → globale. La variable self est toujours disponible et est fournie comme option pour accéder aux membres de la classe, mais n'est pas toujours nécessaire (et ne devrait pas être envoyée comme premier argument de la fonction, contrairement à Python).

func my_function(a, b):

print(a)

print(b)

return a + b # Return is optional; without it 'null' is returned.

Une fonction peut return à tout moment. La valeur de retour par défaut est null.

If a function contains only one line of code, it can be written on one line:

func square(a): return a * a

func hello_world(): print("Hello World")

func empty_function(): pass

Les fonctions peuvent également avoir une spécification de type pour les arguments et pour les valeurs retournées. Les types peuvent être ajoutés aux arguments de la même manière que pour les variables :

func my_function(a: int, b: String):

pass

Si l'argument d'une fonction a une valeur par défaut, il est possible d'inférer le type :

func my_function(int_arg := 42, String_arg := "string"):

pass

Le type de retour de la fonction peut être spécifié après la liste d'arguments en utilisant le jeton de flèche (->) :

func my_int_function() -> int:

return 0

Les fonctions qui ont un type de retour doivent retourner une valeur appropriée. Paramétrer le type d'une fonction à void signifie qu'elle ne retournera rien. Les fonctions vides peuvent retourner à l'avance en utilisant le mot-clé return, mais elles ne peuvent pas retourner de valeurs.

func void_function() -> void:

return # Can't return a value.

Note

Les fonctions non-vides doivent toujours retourner une valeur, donc si votre code a des instructions de branchement (comme une construction if/else), tous les chemins possibles doivent avoir un retour. Par exemple, si vous avez un return à l'intérieur d'un bloc if mais pas après, l'éditeur affichera une erreur car si le bloc n'est pas exécuté, la fonction n'aura pas de valeur valide à retourner.

Fonctions de référencement¶

Functions are first-class items in terms of the Callable object. Referencing a function by name without calling it will automatically generate the proper callable. This can be used to pass functions as arguments.

func map(arr: Array, function: Callable) -> Array:

var result = []

for item in arr:

result.push_back(function.call(item))

return result

func add1(value: int) -> int:

return value + 1;

func _ready() -> void:

var my_array = [1, 2, 3]

var plus_one = map(my_array, add1)

print(plus_one) # Prints [2, 3, 4].

Note

Callables must be called with the call method. You cannot use

the () operator directly. This behavior is implemented to avoid

performance issues on direct function calls.

Lambda functions¶

Lambda functions allow you to declare functions that do not belong to a class. Instead a Callable object is created and assigned to a variable directly. This can be useful to create Callables to pass around without polluting the class scope.

var lambda = func(x): print(x)

lambda.call(42) # Prints "42"

Lambda functions can be named for debugging purposes:

var lambda = func my_lambda(x):

print(x)

Lambda functions capture the local environment. Local variables are passed by value, so they won't be updated in the lambda if changed in the local function:

var x = 42

var my_lambda = func(): print(x)

my_lambda.call() # Prints "42"

x = "Hello"

my_lambda.call() # Prints "42"

Note

The values of the outer scope behave like constants. Therefore, if you declare an array or dictionary, it can still be modified afterwards.

Fonctions statiques¶

A function can be declared static. When a function is static, it has no access to the instance member variables or self.

A static function has access to static variables. Also static functions are useful to make libraries of helper functions:

static func sum2(a, b):

return a + b

Lambdas cannot be declared static.

See also Static variables and Static constructor.

Instructions et flux de contrôle¶

Les instructions sont standard et peuvent être des affectations, des appels de fonctions, des structure de contrôle, etc (voir ci-dessous). ; utilisé comme séparateur d'instructions est entièrement facultatif.

Expressions¶

Expressions are sequences of operators and their operands in orderly fashion. An expression by itself can be a statement too, though only calls are reasonable to use as statements since other expressions don't have side effects.

Expressions return values that can be assigned to valid targets. Operands to some operator can be another expression. An assignment is not an expression and thus does not return any value.

Here are some examples of expressions:

2 + 2 # Binary operation.

-5 # Unary operation.

"okay" if x > 4 else "not okay" # Ternary operation.

x # Identifier representing variable or constant.

x.a # Attribute access.

x[4] # Subscript access.

x > 2 or x < 5 # Comparisons and logic operators.

x == y + 2 # Equality test.

do_something() # Function call.

[1, 2, 3] # Array definition.

{A = 1, B = 2} # Dictionary definition.

preload("res://icon.png") # Preload builtin function.

self # Reference to current instance.

Identifiers, attributes, and subscripts are valid assignment targets. Other expressions cannot be on the left side of an assignment.

if/else/elif (si / sinon / sinon-si)¶

Les conditions simples sont créées en utilisant la syntaxe if/else/elif. Les parenthèses autour des conditions sont autorisées, mais pas obligatoires. Étant donné la nature de l'indentation par tabulations, elif peut être utilisé à la place de else/if pour maintenir un niveau d'indentation raisonnable.

if (expression):

statement(s)

elif (expression):

statement(s)

else:

statement(s)

Les instructions courtes peuvent être écrites sur la même ligne que la condition :

if 1 + 1 == 2: return 2 + 2

else:

var x = 3 + 3

return x

Parfois, il peut être nécessaire d'affecter une valeur initiale différente, basée sur une expression booléenne. Dans ce cas, les conditions ternaires peuvent être utiles :

var x = (value) if (expression) else (value)

y += 3 if y < 10 else -1

Les expressions conditionnelles ternaires peuvent être imbriquée pour gérer plus de deux cas. Lorsque ces expressions sont imbriquées, il est recommandé de les indenter sur plusieurs lignes pour préserver leur lisibilité :

var count = 0

var fruit = (

"apple" if count == 2

else "pear" if count == 1

else "banana" if count == 0

else "orange"

)

print(fruit) # banana

# Alternative syntax with backslashes instead of parentheses (for multi-line expressions).

# Less lines required, but harder to refactor.

var fruit_alt = \

"apple" if count == 2 \

else "pear" if count == 1 \

else "banana" if count == 0 \

else "orange"

print(fruit_alt) # banana

You may also wish to check if a value is contained within something. You can

use an if statement combined with the in operator to accomplish this:

# Check if a letter is in a string.

var text = "abc"

if 'b' in text: print("The string contains b")

# Check if a variable is contained within a node.

if "varName" in get_parent(): print("varName is defined in parent!")

while¶

Simple loops are created by using while syntax. Loops can be broken

using break or continued using continue (which skips to the next

iteration of the loop without executing any further code in the current iteration):

while (expression):

statement(s)

for¶

Pour itérer à travers une plage, telle qu'un tableau ou une table, une boucle for est utilisée. Lors de l'itération dans un tableau, l'élément courant du tableau est stocké dans la variable de la boucle. Lors de l'itération sur un dictionnaire, la key est stockée dans la variable de la boucle.

for x in [5, 7, 11]:

statement # Loop iterates 3 times with 'x' as 5, then 7 and finally 11.

var dict = {"a": 0, "b": 1, "c": 2}

for i in dict:

print(dict[i]) # Prints 0, then 1, then 2.

for i in range(3):

statement # Similar to [0, 1, 2] but does not allocate an array.

for i in range(1, 3):

statement # Similar to [1, 2] but does not allocate an array.

for i in range(2, 8, 2):

statement # Similar to [2, 4, 6] but does not allocate an array.

for i in range(8, 2, -2):

statement # Similar to [8, 6, 4] but does not allocate an array.

for c in "Hello":

print(c) # Iterate through all characters in a String, print every letter on new line.

for i in 3:

statement # Similar to range(3).

for i in 2.2:

statement # Similar to range(ceil(2.2)).

If you want to assign values on an array as it is being iterated through, it

is best to use for i in array.size().

for i in array.size():

array[i] = "Hello World"

The loop variable is local to the for-loop and assigning to it will not change the value on the array. Objects passed by reference (such as nodes) can still be manipulated by calling methods on the loop variable.

for string in string_array:

string = "Hello World" # This has no effect

for node in node_array:

node.add_to_group("Cool_Group") # This has an effect

match¶

L'instruction match est utilisée pour réaliser un branchement de l’exécution d'un programme. Elle est semblable à l'instruction switch présente en beaucoup d'autres langages mais elle procure cependant quelques fonctionnalités supplémentaires.

Avertissement

match is more type strict than the == operator. For example 1 will not match 1.0. The only exception is String vs StringName matching:

for example, the String "hello" is considered equal to the StringName &"hello".

Basic syntax¶

match <expression>:

<pattern(s)>:

<block>

<pattern(s)> when <guard expression>:

<block>

<...>

Crash-course for people who are familiar with switch statements¶

Remplacez

switchparmatch.Supprimer

case.Remove any

breaks.Remplacer

defaultpar un unique underscore (_).

Control flow¶

The patterns are matched from top to bottom.

If a pattern matches, the first corresponding block will be executed. After that, the execution continues below the match statement.

Note

The special continue behavior in match supported in 3.x was removed in Godot 4.0.

The following pattern types are available:

- Literal pattern

Matches a literal:

match x: 1: print("We are number one!") 2: print("Two are better than one!") "test": print("Oh snap! It's a string!")

- Expression pattern

Matches a constant expression, an identifier, or an attribute access (

A.B):match typeof(x): TYPE_FLOAT: print("float") TYPE_STRING: print("text") TYPE_ARRAY: print("array")

- Motif générique (joker/wildcard)

Cette expression correspond à toute possibilité. Elle est écrite sous la forme d'un simple underscore (_).

Elle peut être utilisée comme l’équivalent de

defaultde l'expressionswitchdans d'autres langages :match x: 1: print("It's one!") 2: print("It's one times two!") _: print("It's not 1 or 2. I don't care to be honest.")

- Expression de liaison

Une expression de liaison introduit une nouvelle variable. Comme le caractère joker (wildcard), elle correspond à toutes les possibilités - et donne aussi un nom à cette valeur. Elle est particulièrement utile avec les tableaux et les dictionnaires :

match x: 1: print("It's one!") 2: print("It's one times two!") var new_var: print("It's not 1 or 2, it's ", new_var)

- Modèle de tableau

Elle correspond à un tableau. Chaque élément du modèle de tableau est un modèle lui-même, de sorte que vous pouvez les imbriquer.

La longueur du tableau est d'abord testée, elle doit être de la même taille que l'expression, sinon cette dernière ne correspondra pas.

Tableau ouvert : Un tableau peut être plus grand que l'expression en faisant de

..la dernière sous-expression.Chaque sous-expression doit être séparée par des virgules.

match x: []: print("Empty array") [1, 3, "test", null]: print("Very specific array") [var start, _, "test"]: print("First element is ", start, ", and the last is \"test\"") [42, ..]: print("Open ended array")

- Modèle de dictionnaire

Fonctionne de la même manière que le modèle du tableau. Chaque clé doit être une expression constante.

La taille du dictionnaire est d'abord testée, elle doit être de la même taille que l'expression, sinon l'expression ne correspondra pas.

Dictionnaire ouvert : Un dictionnaire peut être plus grand que l'expression en faisant de

..le dernier sous-modèle.Chaque sous-expression doit être séparée par des virgules.

Si vous ne spécifiez pas de valeur, seule l'existence de la clé est vérifiée.

Une expression de valeur est séparée de l'expression de clé par un

:.match x: {}: print("Empty dict") {"name": "Dennis"}: print("The name is Dennis") {"name": "Dennis", "age": var age}: print("Dennis is ", age, " years old.") {"name", "age"}: print("Has a name and an age, but it's not Dennis :(") {"key": "godotisawesome", ..}: print("I only checked for one entry and ignored the rest")

- Expressions multiples

Vous pouvez également spécifier plusieurs expressions séparées par une virgule. Ces expressions ne peuvent être des expressions de liaisons.

match x: 1, 2, 3: print("It's 1 - 3") "Sword", "Splash potion", "Fist": print("Yep, you've taken damage")

Pattern guards¶

Only one branch can be executed per match. Once a branch is chosen, the rest are not checked.

If you want to use the same pattern for multiple branches or to prevent choosing a branch with too general pattern,

you can specify a guard expression after the list of patterns with the when keyword:

match point:

[0, 0]:

print("Origin")

[_, 0]:

print("Point on X-axis")

[0, _]:

print("Point on Y-axis")

[var x, var y] when y == x:

print("Point on line y = x")

[var x, var y] when y == -x:

print("Point on line y = -x")

[var x, var y]:

print("Point (%s, %s)" % [x, y])

If there is no matching pattern for the current branch, the guard expression is not evaluated and the patterns of the next branch are checked.

If a matching pattern is found, the guard expression is evaluated.

If it's true, then the body of the branch is executed and

matchends.If it's false, then the patterns of the next branch are checked.

Classes¶

Par défaut, tous les fichiers scripts sont des classes sans nom. Dans ce cas, vous pouvez uniquement les référencer en utilisant le chemin du fichier, en utilisant un chemin relatif ou un chemin absolu. Par exemple, si vous nommez un fichier de script character.gd :

# Inherit from 'character.gd'.

extends "res://path/to/character.gd"

# Load character.gd and create a new node instance from it.

var Character = load("res://path/to/character.gd")

var character_node = Character.new()

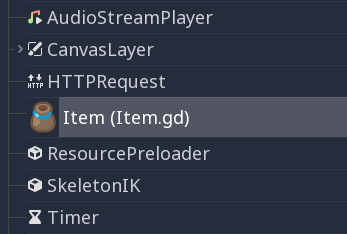

Enregistrement de classes nommées¶

You can give your class a name to register it as a new type in Godot's

editor. For that, you use the class_name keyword. You can optionally use

the @icon annotation with a path to an image, to use it as an icon. Your

class will then appear with its new icon in the editor:

# item.gd

@icon("res://interface/icons/item.png")

class_name Item

extends Node

Voici un exemple de fichier de classe :

# Saved as a file named 'character.gd'.

class_name Character

var health = 5

func print_health():

print(health)

func print_this_script_three_times():

print(get_script())

print(ResourceLoader.load("res://character.gd"))

print(Character)

If you want to use extends too, you can keep both on the same line:

class_name MyNode extends Node

Note

Godot initializes non-static variables every time you create an instance, and this includes arrays and dictionaries. This is in the spirit of thread safety, since scripts can be initialized in separate threads without the user knowing.

Héritage¶

Une classe (stockée sous forme de fichier) peut hériter de :

Une classe globale.

Un autre fichier de classe.

Une classe interne à l'intérieur d'un autre fichier de classe.

L'héritage multiple n'est pas autorisé.

L'héritage utilise le mot-clé extends :

# Inherit/extend a globally available class.

extends SomeClass

# Inherit/extend a named class file.

extends "somefile.gd"

# Inherit/extend an inner class in another file.

extends "somefile.gd".SomeInnerClass

Note

If inheritance is not explicitly defined, the class will default to inheriting RefCounted.

Pour vérifier si une instance donnée hérite d'une classe donnée, le mot-clé is peut être utilisé :

# Cache the enemy class.

const Enemy = preload("enemy.gd")

# [...]

# Use 'is' to check inheritance.

if entity is Enemy:

entity.apply_damage()

To call a function in a super class (i.e. one extend-ed in your current

class), use the super keyword:

super(args)

This is especially useful because functions in extending classes replace

functions with the same name in their super classes. If you still want to

call them, you can use super:

func some_func(x):

super(x) # Calls the same function on the super class.

If you need to call a different function from the super class, you can specify the function name with the attribute operator:

func overriding():

return 0 # This overrides the method in the base class.

func dont_override():

return super.overriding() # This calls the method as defined in the base class.

Avertissement

One of the common misconceptions is trying to override non-virtual engine methods

such as get_class(), queue_free(), etc. This is not supported for technical reasons.

In Godot 3, you can shadow engine methods in GDScript, and it will work if you call this method in GDScript. However, the engine will not execute your code if the method is called inside the engine on some event.

In Godot 4, even shadowing may not always work, as GDScript optimizes native method calls.

Therefore, we added the NATIVE_METHOD_OVERRIDE warning, which is treated as an error by default.

We strongly advise against disabling or ignoring the warning.

Note that this does not apply to virtual methods such as _ready(), _process() and others

(marked with the virtual qualifier in the documentation and the names start with an underscore).

These methods are specifically for customizing engine behavior and can be overridden in GDScript.

Signals and notifications can also be useful for these purposes.

Constructeur de classe¶

The class constructor, called on class instantiation, is named _init. If you

want to call the base class constructor, you can also use the super syntax.

Note that every class has an implicit constructor that it's always called

(defining the default values of class variables). super is used to call the

explicit constructor:

func _init(arg):

super("some_default", arg) # Call the custom base constructor.

Ceci est mieux expliqué par des exemples. Disons que nous avons ce scénario :

# state.gd (inherited class).

var entity = null

var message = null

func _init(e=null):

entity = e

func enter(m):

message = m

# idle.gd (inheriting class).

extends "state.gd"

func _init(e=null, m=null):

super(e)

# Do something with 'e'.

message = m

Il y a plusieurs choses à garder à l'esprit ici :

If the inherited class (

state.gd) defines a_initconstructor that takes arguments (ein this case), then the inheriting class (idle.gd) must define_initas well and pass appropriate parameters to_initfromstate.gd.idle.gdcan have a different number of arguments than the base classstate.gd.In the example above,

epassed to thestate.gdconstructor is the sameepassed in toidle.gd.If

idle.gd's_initconstructor takes 0 arguments, it still needs to pass some value to thestate.gdbase class, even if it does nothing. This brings us to the fact that you can pass expressions to the base constructor as well, not just variables, e.g.:# idle.gd func _init(): super(5)

Static constructor¶

A static constructor is a static function _static_init that is called automatically

when the class is loaded, after the static variables have been initialized:

static var my_static_var = 1

static func _static_init():

my_static_var = 2

A static constructor cannot take arguments and must not return any value.

Classes internes¶

Un fichier de classe peut contenir des classes internes. Les classes internes sont définies à l'aide du mot-clé class. Ils sont instanciés à l'aide de la fonction ClassName.new().

# Inside a class file.

# An inner class in this class file.

class SomeInnerClass:

var a = 5

func print_value_of_a():

print(a)

# This is the constructor of the class file's main class.

func _init():

var c = SomeInnerClass.new()

c.print_value_of_a()

Les classes comme ressources¶

Les classes stockées en tant que fichiers sont traitées comme ressources. Elles doivent être chargées à partir du disque pour y accéder à partir d'autres classes. Cela se fait soit à l'aide des fonctions load ou preload (voir ci-dessous). L'instanciation d'une ressource de classe chargée se fait en appelant la fonction new sur l'objet de classe :

# Load the class resource when calling load().

var MyClass = load("myclass.gd")

# Preload the class only once at compile time.

const MyClass = preload("myclass.gd")

func _init():

var a = MyClass.new()

a.some_function()

Exports¶

Note

La documentation à propos des exports a été déplacé vers GDScript exported properties.

Properties (setters and getters)¶

Sometimes, you want a class' member variable to do more than just hold data and actually perform some validation or computation whenever its value changes. It may also be desired to encapsulate its access in some way.

For this, GDScript provides a special syntax to define properties using the set and get

keywords after a variable declaration. Then you can define a code block that will be executed

when the variable is accessed or assigned.

Example:

var milliseconds: int = 0

var seconds: int:

get:

return milliseconds / 1000

set(value):

milliseconds = value * 1000

Note

Unlike setget in previous Godot versions, the properties setter and getter are always called (except as noted below),

even when accessed inside the same class (with or without prefixing with self.). This makes the behavior

consistent. If you need direct access to the value, use another variable for direct access and make the property

code use that name.

Alternative syntax¶

Also there is another notation to use existing class functions if you want to split the code from the variable declaration or you need to reuse the code across multiple properties (but you can't distinguish which property the setter/getter is being called for):

var my_prop:

get = get_my_prop, set = set_my_prop

This can also be done in the same line:

var my_prop: get = get_my_prop, set = set_my_prop

The setter and getter must use the same notation, mixing styles for the same variable is not allowed.

Note

You cannot specify type hints for inline setters and getters. This is done on purpose to reduce the boilerplate. If the variable is typed, then the setter's argument is automatically of the same type, and the getter's return value must match it. Separated setter/getter functions can have type hints, and the type must match the variable's type or be a wider type.

When setter/getter is not called¶

When a variable is initialized, the value of the initializer will be written directly to the variable.

Including if the @onready annotation is applied to the variable.

Using the variable's name to set it inside its own setter or to get it inside its own getter will directly access the underlying member, so it won't generate infinite recursion and saves you from explicitly declaring another variable:

signal changed(new_value)

var warns_when_changed = "some value":

get:

return warns_when_changed

set(value):

changed.emit(value)

warns_when_changed = value

This also applies to the alternative syntax:

var my_prop: set = set_my_prop

func set_my_prop(value):

my_prop = value # No infinite recursion.

Avertissement

The exception does not propagate to other functions called in the setter/getter. For example, the following code will cause an infinite recursion:

var my_prop:

set(value):

set_my_prop(value)

func set_my_prop(value):

my_prop = value # Infinite recursion, since `set_my_prop()` is not the setter.

Mode tool(outil)¶

By default, scripts don't run inside the editor and only the exported

properties can be changed. In some cases, it is desired that they do run

inside the editor (as long as they don't execute game code or manually

avoid doing so). For this, the @tool annotation exists and must be

placed at the top of the file:

@tool

extends Button

func _ready():

print("Hello")

Voir Exécuter le code dans l'éditeur pour plus d'informations.

Avertissement

Faites attention en supprimant des nœuds avec queue_free() ou free() dans un script outil (en particulier le propriétaire du script). Puisque les scripts outils s'exécutent dans l'éditeur, une erreur pourrait le faire crasher.

Gestion de la mémoire¶

Godot implements reference counting to free certain instances that are no longer

used, instead of a garbage collector, or requiring purely manual management.

Any instance of the RefCounted class (or any class that inherits

it, such as Resource) will be freed automatically when no longer

in use. For an instance of any class that is not a RefCounted

(such as Node or the base Object type), it will

remain in memory until it is deleted with free() (or queue_free()

for Nodes).

Note

If a Node is deleted via free() or queue_free(),

all of its children will also recursively be deleted.

To avoid reference cycles that can't be freed, a WeakRef function is provided for creating weak references, which allow access to the object without preventing a RefCounted from freeing. Here is an example:

extends Node

var my_file_ref

func _ready():

var f = FileAccess.open("user://example_file.json", FileAccess.READ)

my_file_ref = weakref(f)

# the FileAccess class inherits RefCounted, so it will be freed when not in use

# the WeakRef will not prevent f from being freed when other_node is finished

other_node.use_file(f)

func _this_is_called_later():

var my_file = my_file_ref.get_ref()

if my_file:

my_file.close()

Alternativement, quand vous n'utilisez pas de références, le is_instance_valid(instance) peut être utilisé pour vérifier si un objet a été libéré.

Signaux¶

Les signaux sont un outil permettant d’émettre des messages à partir d’un objet auquel d’autres objets peuvent réagir. Pour créer des signaux personnalisés pour une classe, utilisez le mot-clé signal.

extends Node

# A signal named health_depleted.

signal health_depleted

Note

Les signaux sont comme des fonctions de rappel. Ils remplissent également le rôle d'Observateurs, un patron de conception courant en programmation. Pour plus d'informations, lisez le tutoriel sur les Observateurs (en anglais), de l'e-book Game Programming Patterns.

You can connect these signals to methods the same way you connect built-in signals of nodes like Button or RigidBody3D.

In the example below, we connect the health_depleted signal from a

Character node to a Game node. When the Character node emits the

signal, the game node's _on_character_health_depleted is called:

# game.gd

func _ready():

var character_node = get_node('Character')

character_node.health_depleted.connect(_on_character_health_depleted)

func _on_character_health_depleted():

get_tree().reload_current_scene()

Vous pouvez émettre autant d'arguments que vous souhaitez avec un signal.

Voici un exemple où cela est utile. Si nous voulons ajouter une barre de vie qui s'anime quand les points de vie changent, mais nous souhaitons séparer l'interface utilisateur du joueur dans notre arbre de scène.

In our character.gd script, we define a health_changed signal and emit

it with Signal.emit(), and from

a Game node higher up our scene tree, we connect it to the Lifebar using

the Signal.connect() method:

# character.gd

...

signal health_changed

func take_damage(amount):

var old_health = health

health -= amount

# We emit the health_changed signal every time the

# character takes damage.

health_changed.emit(old_health, health)

...

# lifebar.gd

# Here, we define a function to use as a callback when the

# character's health_changed signal is emitted.

...

func _on_Character_health_changed(old_value, new_value):

if old_value > new_value:

progress_bar.modulate = Color.RED

else:

progress_bar.modulate = Color.GREEN

# Imagine that `animate` is a user-defined function that animates the

# bar filling up or emptying itself.

progress_bar.animate(old_value, new_value)

...

Dans le nœud Game, on récupère les nœuds Character et Lifebar puis on connecte le personnage, qui émet le signal, au récepteur c'est-à-dire Lifebar dans notre cas.

# game.gd

func _ready():

var character_node = get_node('Character')

var lifebar_node = get_node('UserInterface/Lifebar')

character_node.health_changed.connect(lifebar_node._on_Character_health_changed)

Cela permet alors à la Lifebar de réagir aux changements de points de vie sans avoir à la coupler au nœud Character.

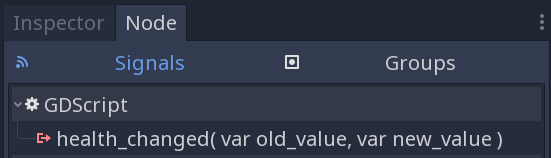

Il est possible d'ajouter des arguments optionnels entre parenthèses après la définition du signal :

# Defining a signal that forwards two arguments.

signal health_changed(old_value, new_value)

Ces arguments seront affichés dans le dock Nœud et Godot les utilisera pour générer les fonctions de rappel automatiquement pour vous. Dans tous les cas, vous pouvez émettre autant d'arguments que vous souhaitez avec vos signaux ; c'est à vous d'émettre les bonnes valeurs.

GDScript peut lier un tableau de valeurs à des connexions entre un signal et une méthode. Lorsque le signal est émis, la méthode de rappel reçoit les valeurs liées. Ces arguments liés sont uniques pour chaque connexion et les valeurs resteront les mêmes.

Vous pouvez utiliser ces arguments pour ajouter des informations supplémentaires à la connexion si le signal émit ne vous donne pas accès à toutes les informations dont vous avez besoin.

À partir de l'exemple présenté plus haut, nous allons afficher une liste des dégâts reçus par chaque personnage à l'écran, par exemple Player1 took 22 damage.. Le signal health_changed ne nous donne pas le nom du personnage qui a pris des dégâts. Alors, quand on connectera le signal à la console en jeu, il faudra ajouter le nom du personnage parmi les arguments du signal émit :

# game.gd

func _ready():

var character_node = get_node('Character')

var battle_log_node = get_node('UserInterface/BattleLog')

character_node.health_changed.connect(battle_log_node._on_Character_health_changed, [character_node.name])

Le nœud BattleLog recevra chaque élément dans les paramètres de sa fonction de rappel :

# battle_log.gd

func _on_Character_health_changed(old_value, new_value, character_name):

if not new_value <= old_value:

return

var damage = old_value - new_value

label.text += character_name + " took " + str(damage) + " damage."

Awaiting for signals or coroutines¶

The await keyword can be used to create coroutines

which wait until a signal is emitted before continuing execution. Using the await keyword with a signal or a

call to a function that is also a coroutine will immediately return the control to the caller. When the signal is

emitted (or the called coroutine finishes), it will resume execution from the point on where it stopped.

For example, to stop execution until the user presses a button, you can do something like this:

func wait_confirmation():

print("Prompting user")

await $Button.button_up # Waits for the button_up signal from Button node.

print("User confirmed")

return true

In this case, the wait_confirmation becomes a coroutine, which means that the caller also needs to await for it:

func request_confirmation():

print("Will ask the user")

var confirmed = await wait_confirmation()

if confirmed:

print("User confirmed")

else:

print("User cancelled")

Note that requesting a coroutine's return value without await will trigger an error:

func wrong():

var confirmed = wait_confirmation() # Will give an error.

However, if you don't depend on the result, you can just call it asynchronously, which won't stop execution and won't make the current function a coroutine:

func okay():

wait_confirmation()

print("This will be printed immediately, before the user press the button.")

If you use await with an expression that isn't a signal nor a coroutine, the value will be returned immediately and the function won't give the control back to the caller:

func no_wait():

var x = await get_five()

print("This doesn't make this function a coroutine.")

func get_five():

return 5

This also means that returning a signal from a function that isn't a coroutine will make the caller await on that signal:

func get_signal():

return $Button.button_up

func wait_button():

await get_signal()

print("Button was pressed")

Note

Unlike yield in previous Godot versions, you cannot obtain the function state object.

This is done to ensure type safety.

With this type safety in place, a function cannot say that it returns an int while it actually returns a function state object

during runtime.

Mot-clé d'assertion¶

Le mot-clé assert sert à vérifier une condition dans un build de débogage. Cette instruction est ignorée dans un build sans débogage, c'est-à-dire que l'expression passée en argument de assert ne sera pas évaluée dans un projet exporté en mode publication. De ce fait, assert ne doit pas contenir des expressions ayant des effets secondaires. Sinon, le comportement du script variera selon s'il est exécuté dans un build de débogage ou de publication.

# Check that 'i' is 0. If 'i' is not 0, an assertion error will occur.

assert(i == 0)

Lors de l'exécution d'un projet depuis l'éditeur, celui-ci sera mis en pause en cas d'erreur d'assertion.

You can optionally pass a custom error message to be shown if the assertion fails:

assert(enemy_power < 256, "Enemy is too powerful!")

Commentaire¶

Tout ce qui est écrit depuis un

#jusqu'à la fin de la ligne est ignoré et est considéré comme un commentaire.# This is a comment.Astuce

In the Godot script editor, special keywords are highlighted within comments to bring the user's attention to specific comments:

Critical (appears in red):

ALERT,ATTENTION,CAUTION,CRITICAL,DANGER,SECURITYWarning (appears in yellow):

BUG,DEPRECATED,FIXME,HACK,TASK,TBD,TODO,WARNINGNotice (appears in green):

INFO,NOTE,NOTICE,TEST,TESTINGThese keywords are case-sensitive, so they must be written in uppercase for them to be recognized:

The list of highlighted keywords and their colors can be changed in the Text Editor > Theme > Comment Markers section of the Editor Settings.